The twinkling lights, the scent of pine, and the vibrant splash of red and green - Christmas is a feast for the senses, and a significant part of that visual splendour comes from the plants and flowers we so lovingly display. But have you ever stopped to wonder where these botanical traditions truly began? Beyond the festive cheer, many of our beloved Christmas plants carry rich histories, native origins, and cultural significance that pre-date their modern holiday association, often tracing back to ancient rites of the winter solstice.

Let's explore the fascinating, interweaving stories behind the most iconic flora of the season.

The Ancient Greenery: Holly, Ivy, and Mistletoe

The trinity of British and European evergreens - holly, ivy, and mistletoe - are perhaps the deepest-rooted symbols of the season, their significance stretching back thousands of years before Christmas. As plants that stubbornly hold their colour and leaves during the bleakest part of the year, they were powerful symbols of eternal life, hope, and the eventual return of spring for various pre-Christian cultures, including the Celts and Romans.

Holly (Ilex aquifolium)

The glossy, dark-green leaves and vibrant red berries of European Holly are quintessentially Christmassy. This indigenous European plant was sacred to early cultures, and in Celtic mythology, holly was seen as a masculine plant, ruling the dark half of the year as the "Holly King," who would symbolically battle the "Oak King" at the Winter Solstice. People brought holly branches indoors to ward off evil spirits and protect their homes.

With the spread of Christianity, the symbolism was adapted: the sharp, prickly leaves came to represent the Crown of Thorns, and the bright red fruits symbolised the blood of Christ. Despite its pagan roots, holly became a mainstay, its enduring colour embodying life and rebirth.

Ivy (Hedera helix)

Often paired with holly, the clinging, winding nature of Ivy is native to Europe and Western Asia. In pre-Christian traditions, Ivy was considered the feminine counterpart to the masculine holly. In ancient Rome, Ivy was associated with Bacchus (Dionysus), the god of wine, revelry, and fertility, and was used in celebratory wreaths. Its tenacious growth and evergreen nature made it a strong symbol of fidelity, devotion, and immortality.

For early Christians, its tenacious need to cling was reinterpreted as the need to cling to God for support. The pairing of holly and ivy in traditional carols reinforces their ancient status as complimentary symbols of winter life and balance.

Mistletoe (Viscum album)

Mistletoe, the semi-parasitic plant that grows high in the branches of host trees, has perhaps the strongest pagan legacy. To the Celtic Druids, Mistletoe was highly sacred, especially when found growing on an oak tree, and they believed it possessed magical properties—calling it "all heal". It was thought to cure diseases, render poisons harmless, and bring fertility and good luck to a household.

In Norse mythology, Mistletoe is linked to the god Baldur, who was killed by an arrow made from the plant; upon his resurrection, his mother, the goddess of love Frigga, declared Mistletoe a symbol of love and peace, vowing to kiss anyone who passed beneath it. This tradition, combined with the plant's ancient associations with fertility, firmly established the romantic custom of kissing beneath the mistletoe.

The Iconic Poinsettia: A Star of Bethlehem from Mexico

Perhaps the most recognisable Christmas plant, the Poinsettia, with its brilliant red bracts, has a deep and important cultural history far from European shores. This striking plant (Euphorbia pulcherrima) is indigenous to Mexico and Central America.

Before its holiday adoption, it was highly valued by the Aztecs, who called it "Cuetlaxochitl" (pronounced kwet-la-SHO-she), a Nahuatl name meaning "residue flower." The Aztecs utilised its milky-white sap for medicine (to treat fever) and its signature red foliage to create dyes. The plant was first associated with Christian celebrations in 17th-century Mexico, where Franciscan priests used the striking red and green foliage to decorate nativity scenes. It was later introduced to the United States after 1825 by Joel Roberts Poinsett, (hence the name Poinsettia) who was the first U.S. Ambassador to Mexico, and its striking, star-like appearance made it a natural symbol for the Star of Bethlehem

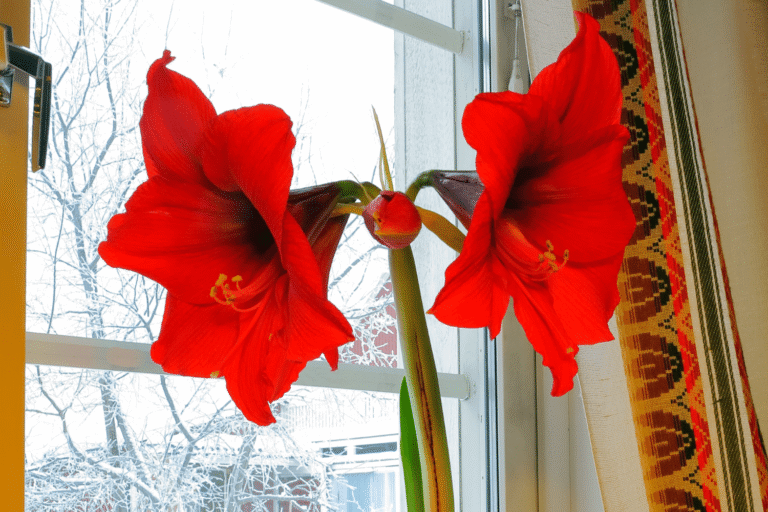

The Majestic Amaryllis: A Dazzling South American Star

The Amaryllis, with its dramatic, trumpet-shaped blooms, is a true showstopper. The flower we recognise is scientifically the genus Hippeastrum, which is native to the tropical and subtropical regions of South America, including Brazil and Peru. These vibrant bulbs were first brought to Europe in the 1700s.

The genus name Hippeastrum translates fittingly to "Knight's Star." Because these South American bulbs can be reliably forced to bloom indoors during the Northern Hemisphere's winter, their dazzling appearance became a perfect, timely centrepiece, representing dazzling beauty and the coming light.

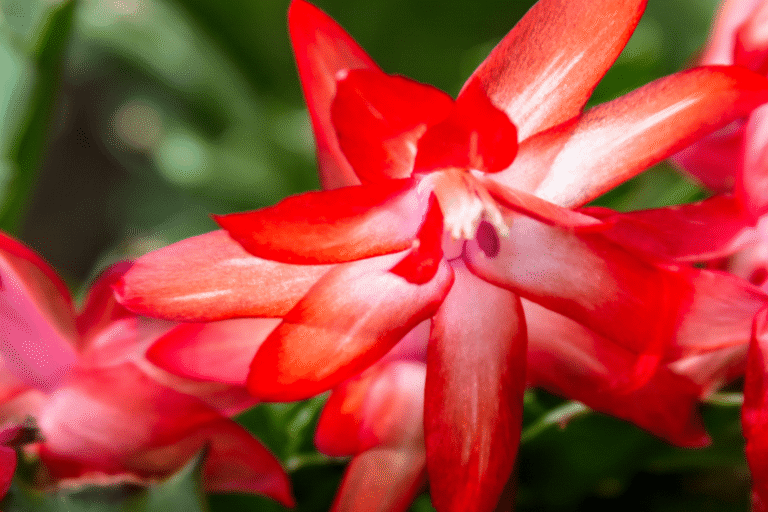

The Cheerful Christmas Cactus: A Rainforest Survivor

Bringing a unique, segmented charm to the holidays, the Christmas Cactus (Schlumbergera spp.) is a resilient succulent. Unlike desert cacti, it is native to the coastal mountains of south-eastern Brazil, where it lives as an epiphyte, clinging to trees in humid rainforests.

It was introduced to Europe in the early 19th century. In its native Southern Hemisphere, the plant flowers around May, giving it the local name "Flor de Maio" (May Flower). When cultivated in the North, its natural blooming cycle aligns with the decreasing daylight hours of late November and December, earning it its festive name and cementing its place as a charming botanical anomaly in the winter décor.

The Enduring Christmas Tree: A Northern Tradition of Life

The Christmas tree, the central symbol of the holiday, carries traditions that are far older than the holiday itself. The trees used - primarily Firs (Abies), Spruces (Picea), and Pines (Pinus) - are evergreens native to temperate and boreal regions across the Northern Hemisphere.

The use of evergreens to symbolise life and ward off evil spirits during midwinter dates back to ancient times. The modern tradition is most directly traced to 16th-century Germany, where families brought decorated fir trees into their homes, originally known as "Paradise Trees." The Indigenous American and First Nations groups across North America, where various species are native, have their own deep histories with these trees, using them as essential sources of shelter and medicine for millennia. The tradition, popularised in the UK in the 19th century thanks to Queen Victoria, remains a powerful, cross-cultural symbol of enduring life during the darkest days of the year.

So, when you buy your festive flora this Christmas, think about their ancient origins and remember that you are continuing a long-held tradition passed down through time, place, religion and the ancestors who lived through the long, dark winters of many generations past – the tradition of bringing foliage indoors to remind us that the spring is just around the corner.

Merry Christmas!